Quantum mechanics is often presented as fundamentally mysterious, especially when it comes to measurement. A quantum system can exist in a superposition of possibilities, yet measurements yield definite outcomes. This apparent tension has motivated a wide range of interpretations, from wavefunction collapse to many-worlds to strongly observer-centered views.

A more modest possibility is that standard quantum mechanics already explains much of this behavior, provided we take seriously the role of large, macroscopic systems. My 2021 paper develops this idea in detail by modeling how measurements unfold when microscopic interactions are amplified into macroscopic records. While I was inspired by some other papers that study similar systems, I think one important idea it dwells on (which others seem to ignore) is that NONE of our measuring apparata are INFINITELY massive – they are just big. The quantum theory of measurement requires that measurement is performed by a classical device – which means it has to be infinitely heavy so as to not have any quantum mechanical indeterminacy at all. We do not have such devices – if they existed, they would turn into black holes. That’s what our universe is set up to do – don’t complain! Quantum mechanics is a theory of OUR universe.

The resulting picture is not radical. It is closer to statistical mechanics than metaphysics.

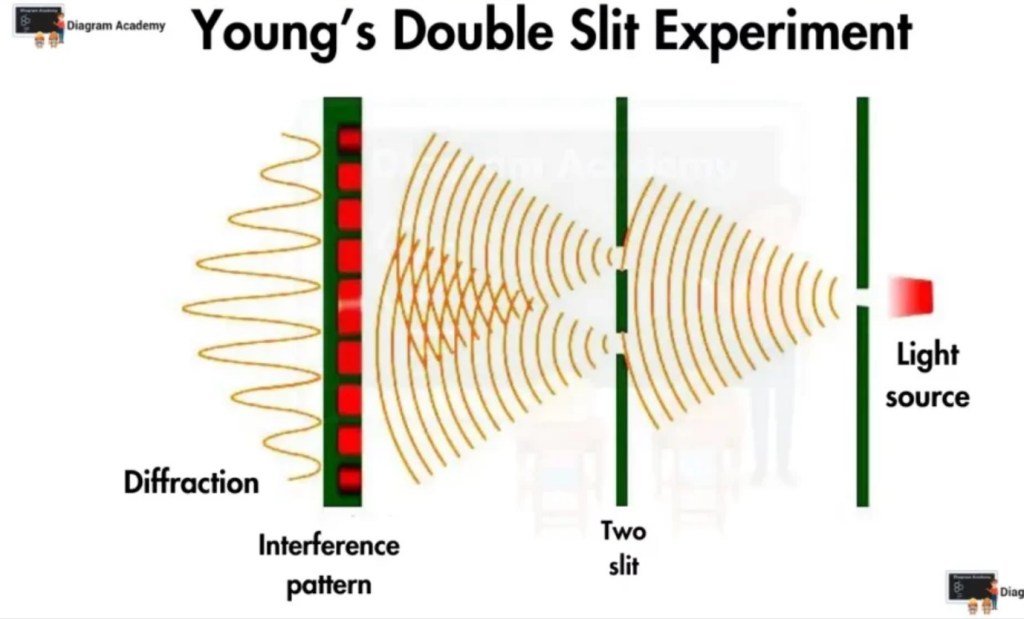

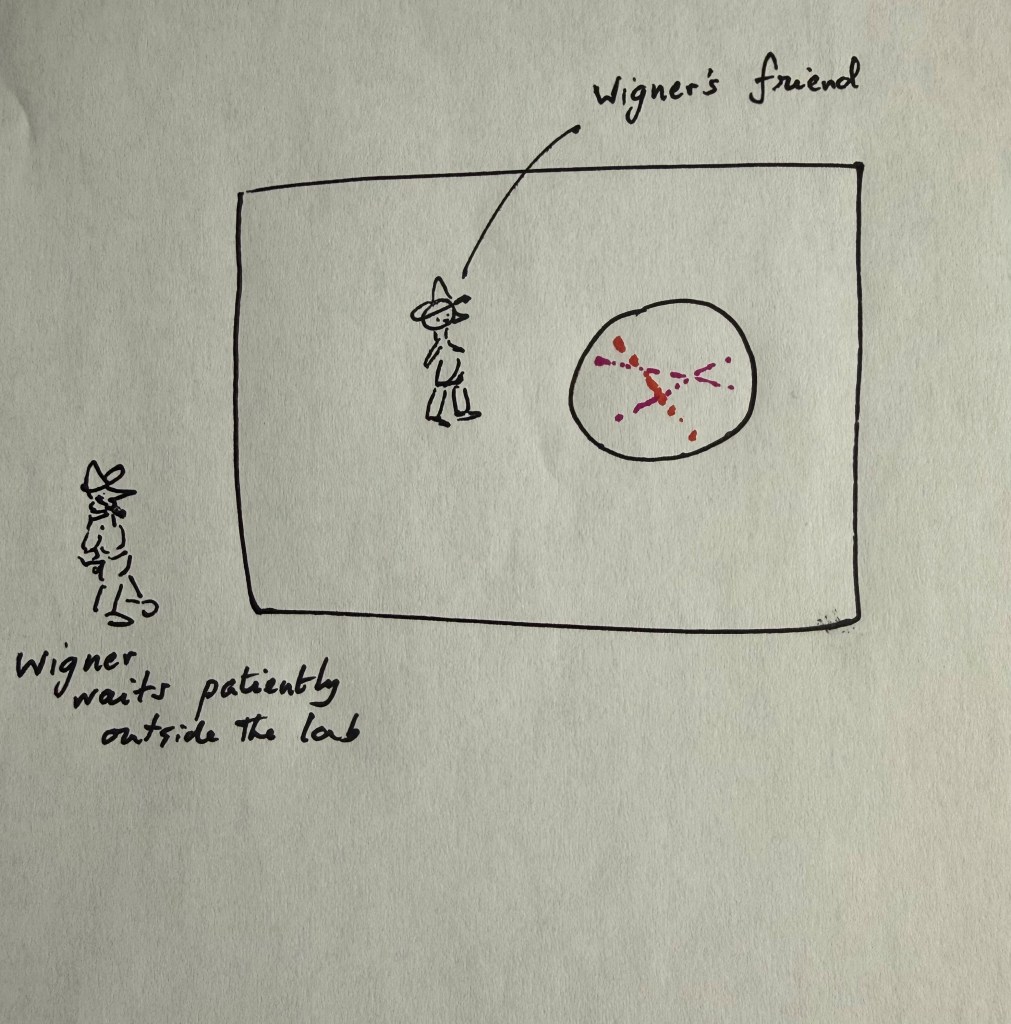

Figure 1. A double-slit schematic showing interference patterns and detection. Source: adapted from Wikipedia (CC BY-SA).

Observers as Physical Systems

A central assumption of the paper is straightforward: observers and measuring devices are physical systems governed by the same quantum laws as everything else. There is no need to introduce special rules for “measurement” or to treat observers as external to the quantum description.

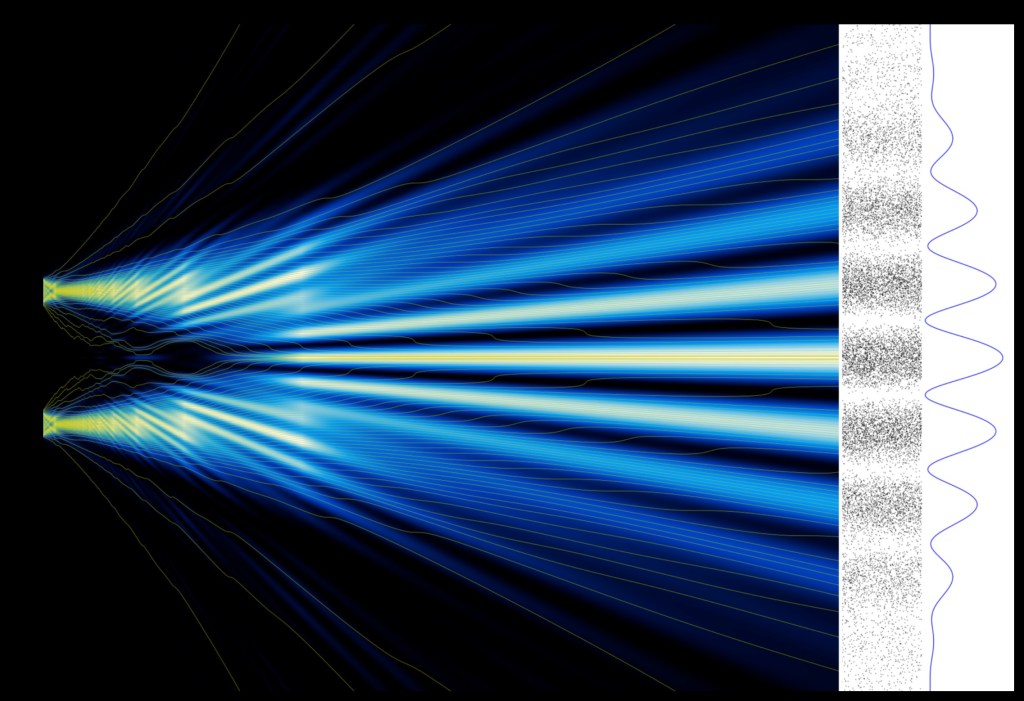

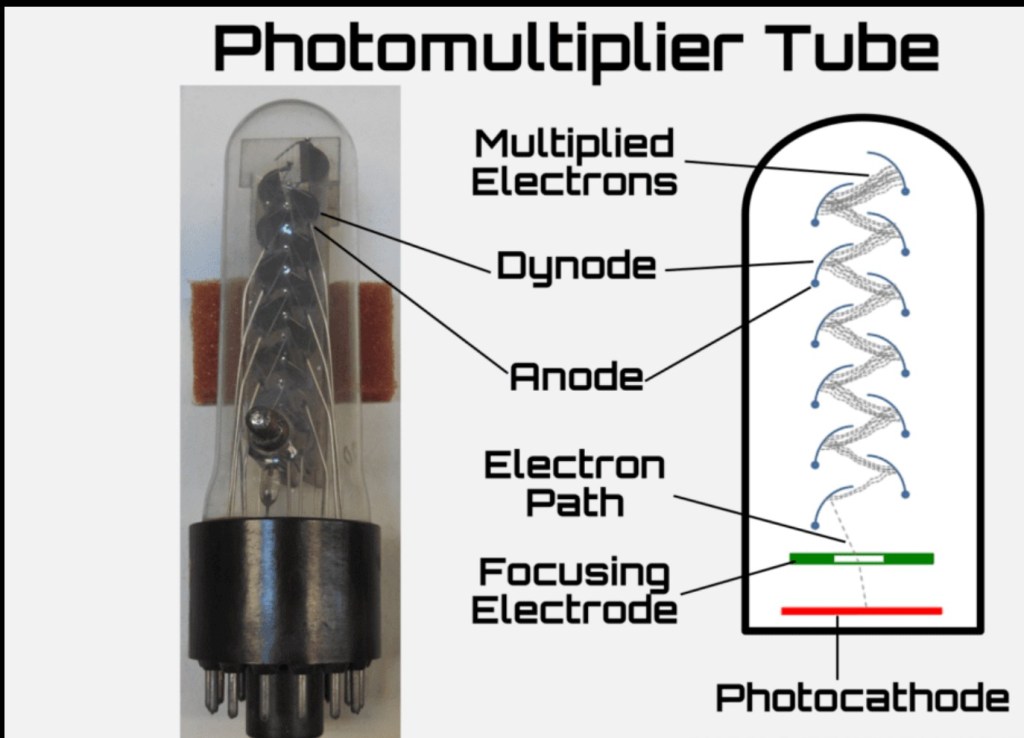

In the double-slit example analyzed in the paper, a single microscopic interaction—an electron scattering a photon—can initiate a cascade inside a detector (like the photomultiplier below). That cascade involves many degrees of freedom: photons, electrons, electronic circuits, and eventually macroscopic readouts.

Figure 2. Microscopic detection leading to macroscopic signals. Illustration adapted from typical detector diagrams.

From a quantum-mechanical perspective, this is simply entanglement spreading through a large system. The quantum state evolves unitarily throughout. Nothing discontinuous occurs.

Why Outcomes Appear Irreversible

If the underlying dynamics are reversible, why do measurements seem irreversible?

The answer given in the paper mirrors familiar arguments from thermodynamics. Once information about an outcome becomes distributed across a large number of degrees of freedom, the number of microscopic configurations consistent with that outcome becomes enormous. The number of configurations corresponding to a precise reversal is exponentially smaller.

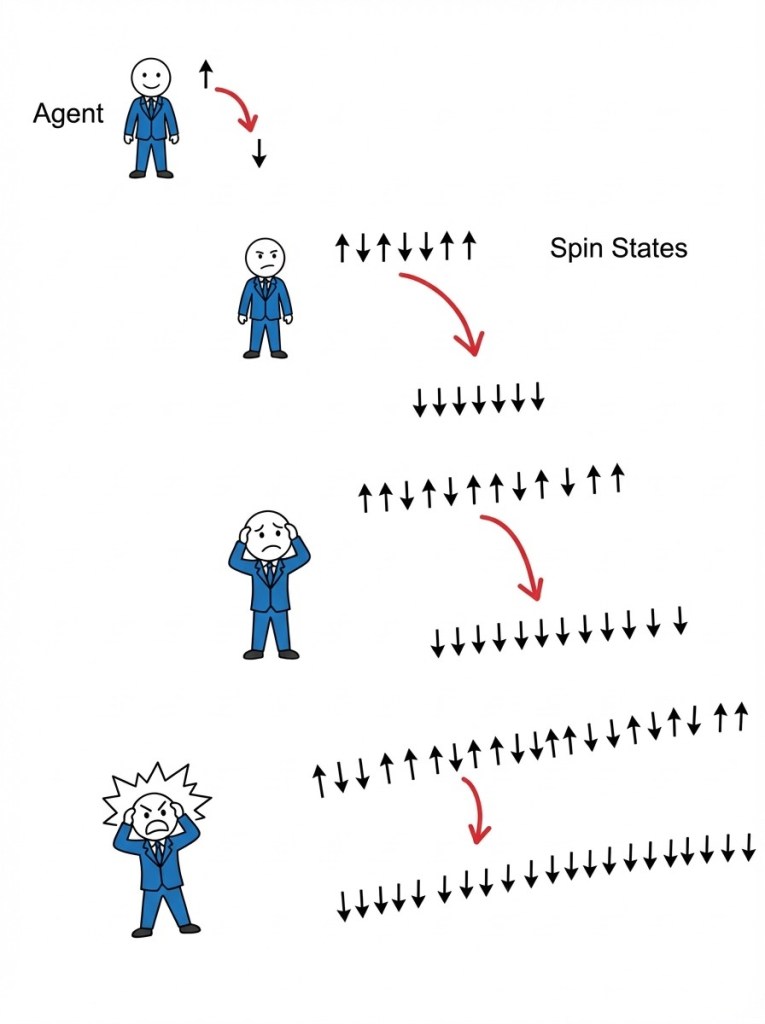

As a result, while reversal is not forbidden by the equations, the timescale for recurrence grows exponentially with the size of the measuring apparatus. For macroscopic systems, these times are vastly longer than any practical or even cosmological timescale. Note our observer is getting increasingly hassled below!

In this sense, wavefunction “collapse” is not actually a useful way to think about measurement. There is no collapse, just a wavefunction with more of its weight attached to one outcome out of several.

Now, why that outcome and not another is indeed an interesting question and that is where the truly ultimate randomness in Nature makes an appearance. In fact, all I need is that one choice becomes the favored one for a very long time. Which one, is a random choice.

Agreement Between Observers

This framework also helps clarify why different observers tend to agree on measurement outcomes.

Once an outcome is recorded in a macroscopic apparatus—stored in detector states, written records, digital files, or memory—any later observer interacting with that apparatus becomes correlated with the same outcome. Disagreement would require all of those correlations to reverse simultaneously, which is statistically implausible for large systems.

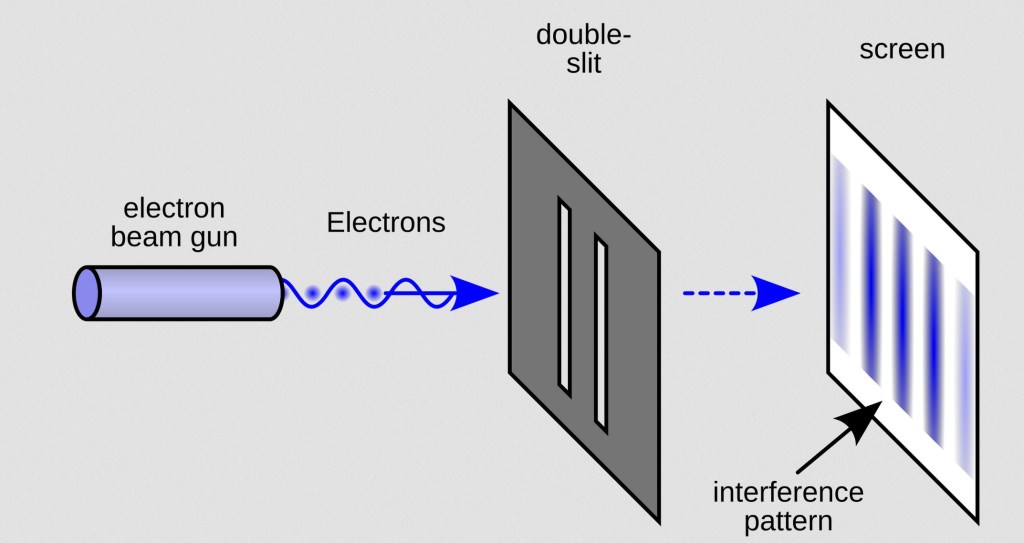

Thus, observer agreement is not an additional postulate. It follows naturally from the dynamics of large entangled systems. Hence, the difficult “paradoxes” supposedly introduced by Wigner’s friend, or Schrodinger’s cat (for that matter) are resolved without the need to add a conscious observer into the picture. We just need reasonably large measuring apparata (a friend in the first case and a reasonably friendly cat in the second).

What Happens to the Alternatives?

If collapse is approximate rather than fundamental, what happens to the alternatives that were not realized?

They are not eliminated, but they become encoded in highly delocalized correlations across the system. In small or carefully controlled systems, such correlations can sometimes be recovered, as demonstrated in quantum eraser and weak-measurement experiments. In larger systems, this information becomes effectively inaccessible.

Figure 4. A schematic for the Wigner’s friend scenario.

This intermediate regime—between fully coherent quantum systems and fully classical ones—is often described as mesoscopic quantum physics, and it remains an active area of experimental (and my) research. Can we “almost” measure something and get traces of an “almost” measurement?

A Note on Interpretations

Some interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as QBism, address measurement problems by treating the quantum state as a description of an agent’s personal expectations rather than a feature of the external world. This avoids certain conceptual puzzles but leaves open questions about shared reality and intersubjective agreement (why do we both agree on any measurement).

The approach outlined here does not require such a move. It treats the quantum state as a physical object and observers as subsystems within it. The appearance of “apparent collapse” and classicality is explained dynamically, rather than being assumed or redefined.

Summary

The picture that emerges is a restrained one:

- Quantum mechanics applies universally.

- Measurements are physical processes involving amplification and entanglement.

- Apparent irreversibility arises from system size and combinatorics, not new laws.

- Observer agreement is a consequence of shared correlations.

Rather than making quantum mechanics more mysterious, this view places it closer to other areas of physics where irreversibility and stability emerge from reversible microscopic laws.

It suggests that many of the puzzles surrounding measurement are not about the limits of quantum theory, but about the scale at which we usually encounter it.

A TECHNICAL ASIDE:

Technical Deep Dive: The Mathematical Analysis

The research demonstrates that wave-function “collapse” is not an external postulate, but a dynamic consequence of a unitary, time-dependent Hamiltonian applied to a large system.

1.

The model treats the detector as a physical subsystem where external energy is used to amplify weak signals. The complete Hermitian Hamiltonian is defined as

In this framework, energy is supplied through interaction vertices to drive a cascade that redistributes energy into a macroscopic number of available states

2.

By applying the Schrödinger equation to the state expansion, the system can be represented as a collection of coupled harmonic oscillators. This leads to a second-order matrix equation:

The matrix is a

symmetric, time-independent matrix with a unique one-skip-tridiagonal structure.

3.

The decay of the initial “un-collapsed” amplitude q1 follows two distinct regimes based on the number of available macroscopic modes :

Short-Term Regime (ST): The decay follows a quadratic, Gaussian-like behavior consistent with Fermi’s Golden Rule, with a decay time scale .

Long-Term Regime (LT): The amplitude eventually falls off exponentially

As (the number of macroscopic states) increases, the collapse of the amplitude to zero becomes effectively instantaneous.

4.

The permanence of measurement is explained by the recurrence time—the time required for the system to fluctuate back to its initial state

. For a system with M participating particles, this time is proportional to . For macroscopic systems, these times vastly exceed multiple lifetimes of the universe, making the result deterministic for all practical observers

.

Leave a reply to Olga Cooperman Cancel reply