I have been planning to write a post about something rather esoteric, called the Unruh effect (and its intellectual descendant, the Hawking effect) and wanted to find a way to explain it to a high-school student. In the process, I discovered a new way to look at the effect, which is now on the arxiv and submitted to a physics journal.

Once I did submit the article, I discovered that the same idea was invented earlier (26 years to be precise) by a group of physicists from TIFR in India – led by the incomparable Thanu Padmanabhan. However, in addition, I also devised an experiment that one could perform to try and test this rather weak effect.

The Unruh effect refers to the work of a really creative fellow called William Unruh (student of John Wheeler’s at Princeton). He published this in – almost 50 years ago. At the time, he was thinking about quantum fields, those ethereal things that pervade all of space and time and that we are all quanta of. Quantum fields can be in their lowest energy or ‘vacuum’ state, which has no ‘physical’ particles, but does have ‘virtual’ particles that seem to pop in and out of existence from nowhere. These virtual particles don’t change the total number of particles (plus antiparticles) in the world, ever. This state, called the quantum ‘vacuum’ has been the subject of much study for several years. One of the interesting conundrums of modern physics is that the amount of energy in the vacuum that one calculates from theory outstrips the actual amount of energy in the vacuum we see around us by a factor of

! The discrepancy between the theoretical prediction and the actual value is sometimes referred to as the ‘worst prediction of modern physics’.

But enough about the ‘worst prediction’. Unruh discovered something else that was really puzzling.

He studied what would happen if an observer sitting in a laboratory created a quantum field in the vacuum state and also allowed another observer to accelerate past him. He calculated, from quantum field theory, that the accelerated observer would see a burst of radiation with a spectrum (a frequency dependence) which would correspond to a temperature the acceleration.

This was quite a surprise. Then, Stephen Hawking had the bright idea that since Einstein had shown that there is an equivalence between acceleration and gravitation, one would also expect to see a black hole radiate energy with a temperature proportional to where

is the mass of the black hole.

All this is rather puzzling. Why would someone see radiation in what looks like a vacuum?

The reason has to do with the existence of horizons.

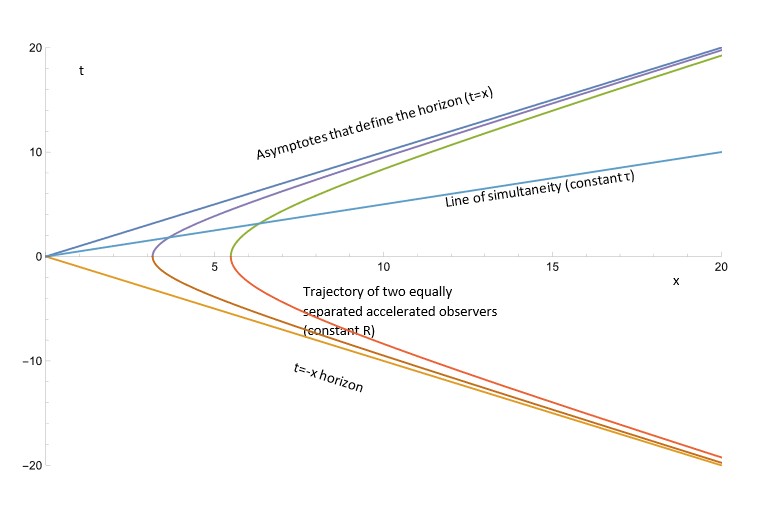

The path of an accelerating observer that starts infinitely far away, traveling initially towards the origin of the coordinate system at the speed of light but accelerating away from the origin is shown in the figure below.

The path is shown on the graph on the left – the scale has been chosen so that the path of light ray would be a line angled at

to the horizontal. The observer starts, infinitely far away to the right, traveling to the left. She is initially traveling at the speed of light. She is, however, accelerating to the

, so this means that she begins slowing down. She finally decelerates to a stop (for the red/green path shown) somewhere near

. Then she continues accelerating to the right and slowly again attains the speed of light. Nothing can, of course, travel faster than light, so her path will gradually reach an angle of

to the horizontal.

To actually compute the path, one needs to learn some special relativity. It’s not particularly difficult, but the diagram above may be understood without knowing how to derive the equation for the path, which is called a hyperbola.

Let’s see what a horizon is. Suppose someone (‘all of us readers’) were standing at . Such a person might shine a flashlight at the observer. Such a light beam’s path, on this graph, would be the

(referred to as the asymptote

in the picture) in the picture. This light would

reach the accelerating observer! In fact, if someone were standing to the left, i.e., at negative

-points at

, and flashed light signals at the accelerating observer,

reach the accelerating observer either.

For our hapless accelerating observer, the universe is bounded by the lines and by a very similar argument

.

These lines define a horizon.

Our accelerating observer would see the lines as her version of ‘infinitely’ far away! That is why those are called horizons.

OK, so her coordinate system would be scrunched up – she would approximately match the ‘lab’-coordinates to the extreme right, but would have distinct horizons (an infinite distance away for her) at .

One can make a coordinate transformation between our coordinates and her coordinates. Since this is a relativistic world and since she is moving rather fast, you could assume that her sense of time (her ‘proper’-time) would also be different. One can now see what would happen if there was someone sitting in our (lab) reference frame at some point that was visible to our traveler. We might send out a particular frequency, but the accelerating observer might see either a higher or lower frequency depending on how fast she is traveling, i.e., which depends on when she receives the signal because her speed keeps changing as she accelerates. That is just because of the usual Doppler effect, with the usual relativistic corrections.

The Doppler effect, for those that might not remember, just encapsulates your experience when you hear an ambulance siren as it comes towards you (‘higher pitch’) and then goes away (‘lower pitch’). If you were accelerating towards a stationary ambulance emitting a siren, you would hear its pitch go up as your speed increases towards it. Conversely, if you were accelerating away from it, you would hear its pitch steadily decrease. Remember, it is the pitch we are talking about here, not the volume, which also goes up or down as you get closer or further away.

Anyway, the accelerating observer would receive these different frequencies, even though we just sent a pure note at her. It turns out that the frequency spectrum of the notes she receives are exactly distributed as Unruh predicted for the entire vacuum spectrum.

The spectrum has nothing to do with the vacuum. It is a consequence of the geometry of the accelerating observer’s coordinates! The vacuum simply has a collection of distinct separate ‘notes’, so it is an uncorrelated sum over these different frequency spectra, all of which have the same shape.

This is exciting and I was able to show how to think of the Hawking radiation for black-holes in the same way. Others have done it in different ways, so this is not particularly new: However, one can design an experiment to try and verify these effects – it doesn’t need us to locate a suitable black hole or prepare a quantum field in a vacuum state.

The proposed experiment is displayed below.

A schematic of the experiment is indicated – positively charged multi-level molecules (set up to be in a particular intermediate energy level) are shot at high speed (close to the velocity of light) at a source of a single frequency. An electric field decelerates, then accelerates the molecules in the opposite direction to a high speed. Once an equilibrium situation is set up, the field (and frequency source) is turned off – the molecules drift at constant speed towards either end of the apparatus where they are classified by the energy they deliver to the targets at the opposite ends (deduced from spikes in electron current flow as they de-ionize). One then obtains the statistics of what wavelength was absorbed at each point on the path – essentially one has the observed frequency at several points on the path. A discrete Fourier transform can now be calculated and compared to the expected spectrum (which is called the Bose distribution).

Now, a note about the title. People used to think that statistical distributions, like the Bose distribution, were descriptions of ‘disorder’. But as this analysis shows, you can obtain such a distribution from a perfectly ordered system – a single frequency in one observer’s coordinates turns out to be a statistical distribution in someone else’s. That is incredible, at least for me and shows how geometry has power that at least I haven’t appreciated!

Leave a reply to V. Balakrishnan Cancel reply