The Painted Ball Trick: Seeing the Connection Between Spin and Statistics

Quantum mechanics is famous for being counter-intuitive. Two of its weirdest features are “spin” and the rules about how identical particles behave when you swap them.

Spin isn’t really things spinning like tops, but it acts a bit like it. The weirdest thing about spin- particles (like electrons) is that if you rotate one by 360 degrees, it’s wave-function doesn’t come back to its starting state. It comes back multiplied by minus one. You have to rotate it twice (720 degrees!) to get back to exactly where you started.

Then there’s statistics. In our everyday world, if I have two identical red billiard balls, ball A and ball B, and I swap their positions, nothing changes. In the quantum world, if you swap two electrons, their combined wavefunction gets multiplied by −1. And alternatively, if you swap two photons, nothing happens to the sign. And what does this have to do with statistics – here’s a simple way to see it (see my post on Fermi-Dirac and Bose statistics). If two identical particles have a wave-function that gets a minus sign if their coordinates are switched, then, the wave-function would be 0 (ZERO) if the particles occupied the same position – this is just the Pauli principle for fermions. A similar argument connects the Bose distribution to identical particles described by a wave-function that does not change sign when their positions are switched.

Now, as far as fermions are concerned, these two things, viz., the −1 from a 360-degree single-particle rotation and the −1 from swapping two particles—seem totally distinct. But what if I told you they are actually the same −1?

There is a beautiful, simple geometric way to connect these two ideas. We just need a little imagination and some paint.

The Single Particle “Headlight”

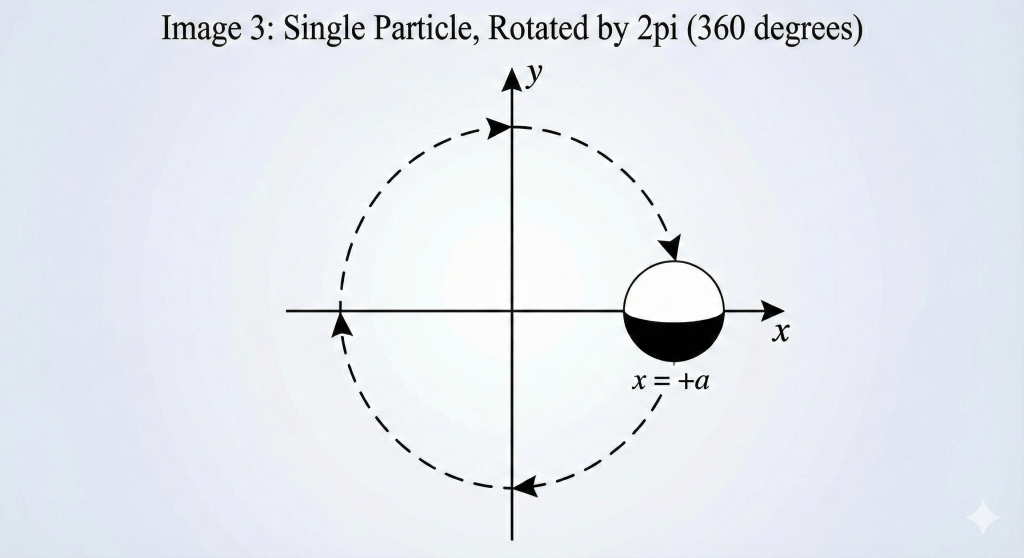

First, let’s visualize that weird 2π rotation. Imagine an electron sitting at rest, on the equator of a sphere – the intersection of that sphere with the x-y plane is shown in all the below pictures. Now, imagine a ball around the electron – it is an imaginary ball, of course. We paint the “front” half (facing the +y direction) white and the “back” half black. See the pictures.

If we want to move this electron (along with the ball, of course) in a circle around a central point, and we want it to face “forward” like a car headlight along its path, the electron has to rotate internally as it moves along the orbit. By the time it finishes a full circle, the “headlight” has also made a full 360-degree rotation.

In quantum math, the operator that rotates a spin- particle by an angle θ looks something like

. If θ is a full circle (2π), we get

, which equals −1.

So, remember this: Rotating a spin- particle by a full circle multiplies its state-vector, i.e., its wave-function, by a factor of -1.

The Two-Particle Swap Trick

Now for the main event. How does this connect to swapping particles?

Let’s take two identical electrons and place them on the x-axis, one at position +a and one at −a.

We need our painted balls again, but with a twist setup:

- The electron on the right (+a) has its white half facing “up” (+y).

- The electron on the left (−a) has its black half facing “up” (+y).

They are anti-aligned visually. (See Image 1 below).

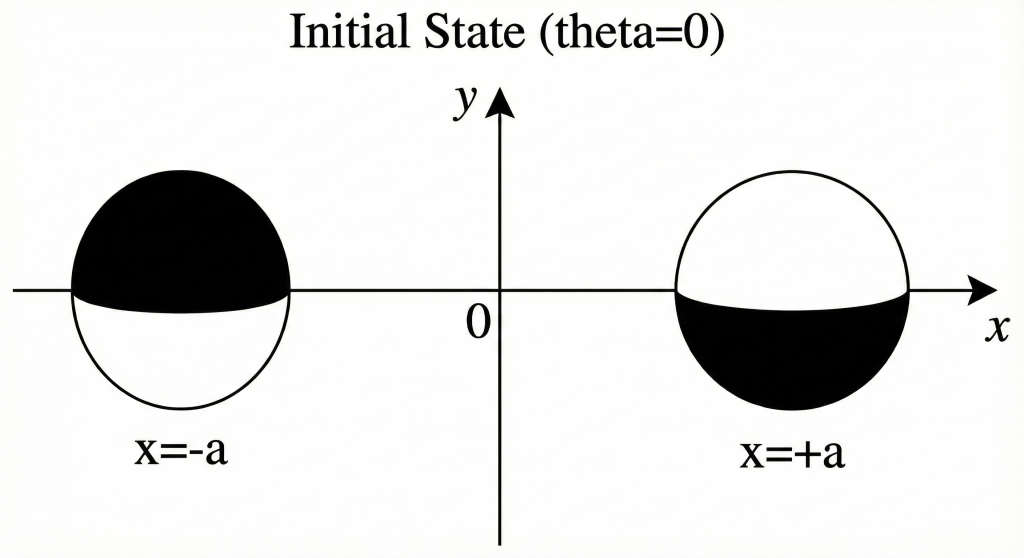

Now, what does it mean to “swap” these particles physically? It means we take the whole system and rotate it by 180 degrees (π radians) around the center point.

Look at the geometric moves in the images below:

Look closely at the final state (Image 3) compared to the initial state (Image 1).

- The particle that was on the right is now on the left. Because it rotated 180 degrees, its white face is now pointing “down”.

- The particle that was on the left is now on the right. Its black face is now pointing “down”. This is shown below.

Because these particles are identical, the final picture looks exactly like the initial picture, just with the particles swapped. The physical act of rotating the system by π is geometrically identical to the act of permutation!

BUT: we have a problem. Yes, the look identical, but the wave-function (state-vector) for the system could have some phase attached to it. The punch line now is that we have this system wrapped around the equator of a sphere – as I said before. We could simply push the path we used to push these electrons, with their funny painted balls, around the equator and push the paths so far north, they go off the sphere – then we compress the path to a point. Now, it is as if we did nothing at all – so the wave-function at the end of this manipulation should indeed be identical to what we started with. The switcheroo here should give us a factor of 1 if we rotate the particles a full revolution around the circle! Does that happen?

The Punchline

We established that a physical swap is just a 180-degree rotation of the system.

If a 360-degree rotation of one particle gives a factor of −1, then a 180-degree rotation of one particle gives a factor of the square root of -1, which is i (or slightly more accurately in operator terms, something that behaves like i).

When we rotate the two-particle system by 180 degrees, we are rotating Particle 1 by 180 degrees AND rotating Particle 2 by 180 degrees.

Particle 1 picks up a factor of i. Particle 2 picks up a factor of i.

The total factor for the system is i×i=−1.

And indeed, if we rotated the particles by 180 degrees again, we’d recover the factor of , as we required.

And there you have it. The reason swapping fermions introduces a minus sign is fundamentally linked to the fact that they are spin-1/2 objects that require a 720-degree rotation to return to normal. A single swap is just half of that journey for two particles simultaneously.

Note another corollary – we cannot do this if we didn’t have these particles on a sphere. If they were on a cylinder, we could never get the paths off the cylinder by sliding the path around. That’s why this argument does not work on a two-dimensional plane and we can have “anyons” with any statistics you desire in two spatial dimensions.

The point I am trying to make is that these properties seem to be a consequence of the fact that we live in three spatial dimensions. In fact, the fact that the particles we see around us are fermions or bosons (in space, I mean, not in peculiar restricted geometries that we could construct) is an indication we do not live in a two-spatial dimensional universe.

Featured image courtesy JasonHise, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a comment